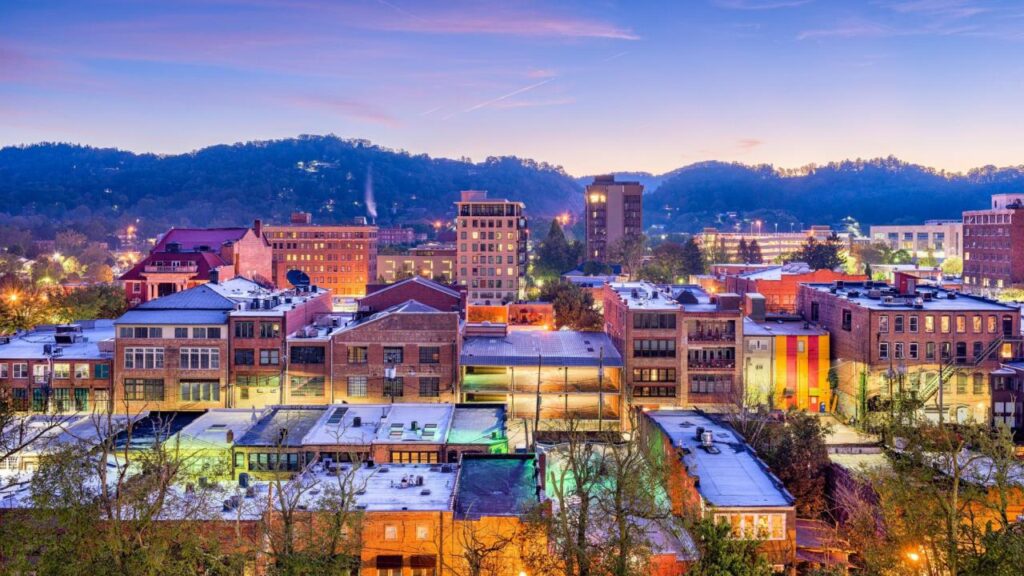

Asheville, NC HOA Management

As the urban hub of Western North Carolina, Asheville has a lot to offer.

From high-end dining to world-class breweries and from endless hiking trails to canoe trips on the French Broad River, residents of Asheville have unlimited options at their disposal. At William Douglas Property Management, we recognize this which is why we work to provide superior HOA management in and around Asheville. Our approach is individualized and tailored to the needs of your residents. We are confident that we can transform the residential community of your dreams into a reality.

Asheville, North Carolina Facts

Asheville, North Carolina, is a city in Buncombe County. Asheville is the county seat, and the 2019 U.S. Census population estimate was 92,870. The city has a total area of 44.93 square miles, per the U.S. Census. Geographically, Asheville has a latitude of 35°35′45″N and longitude of 82°33′10″W. The zip codes for Asheville are 28801, 28802, 28803, 28804, 28805, 28806, 28810, 28813, 28814, 28815, and 28816. The area code for Asheville is 828.

Asheville was incorporated in 1797 and named after North Carolina Governor Samuel Ashe (1725 – 1813). The town was an unsettled frontier outpost when it was first settled, and was the seat of power for the new Buncombe County. It was also the location of the courthouse.

Historic Asheville Population

1800 38 —

1860 502 —

1870 1,400 178.9%

1880 2,616 86.9%

1890 10,235 291.2%

1900 14,694 43.6%

1910 18,762 27.7%

1920 28,504 51.9%

1930 50,193 76.1%

1940 51,310 2.2%

1950 53,000 3.3%

1960 60,192 13.6%

1970 57,929 −3.8%

1980 54,022 −6.7%

1990 61,607 14.0%

2000 68,889 11.8%

2010 83,420 21.1%

2019 92,870 (est.) 11.4%

Per the U.S. Census Bureau:

Population per 2010 Census: 83,420

Male population: 47.8%

Female population: 52.2%

Population under 18 years: 17.8%

Population 65 years & over: 18.1%

High school graduate or higher 2015-2019: 91.7%

Bachelor’s degree or higher 2015-2019: 48.9%

Median home value 2015-2019: $270,400

Owner-occupied: 48.2%

Total households 2015-2019: 40,791

As of the 2012 U.S. Census, there were 12,785 businesses or firms within the City of Asheville.

A Brief Historical Overview of Asheville and the Surrounding Area

Archaeological evidence shows that the Buncombe County area was inhabited as far back as 12,000 years ago. The Cherokee Indians are the first documented inhabitants of the area. The first written documentation of the Cherokee comes from the expedition of Hernando de Soto, a Spanish explorer, in 1540. De Soto was the first European explorer to lead an expedition into the interior of what would become the United States. His expedition entailed searching for gold and a land route to China.

The written documentation of De Soto’s expedition comes from the semi-anonymous work of a man known only as the “Gentleman of Elvas.” He was reportedly a member of the expedition, and his work, True Relation [Relaçam Verdadeira] of the Hardships Suffered by Governor Hernando De Soto & Certain Portuguese Gentlemen During the Discovery of the Providence of Florida, was published in 1557. A report of the expedition published in 1544 by another member of the expedition, Luys Hernández de Biedma, provided additional supporting documentation of the expedition. The diary of De Soto’s secretary, Rodrigo Ranjel, was used as the basis for La historia general y Natural de las Indias, published in 1851, written by Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés. Ranjel’s original diary has been lost to history. Oral histories of the Cherokee Indians have been transcribed as well, and these, too, have documented this initial European and Cherokee encounter in 1540.

The next prominent documentation of Native Americans in the Cherokee Indian region was in 1670, with John Lederer, a German explorer. His expeditions into Virginia and the mountains of North Carolina are documented in his book, The Discoveries of John Lederer in Three Several Marches From Virginia, to the West of Carolina, and Other Parts of the Continent: Begun in March 1669 and ended in September 1670. His expeditions were in search of feasible mountain passes to reach the Pacific. Lederer is supposedly the first European to crest the Blue Ridge Mountains and the first to see the Shenandoah Valley. The maps and other writings of Lederer’s expeditions helped developed the fur trade between European traders and the Cherokee and Catawba Indians. This trade ultimately changed Native American societies forever.

European traders to the Cherokee territory arrived on the heels of Lederer’s expeditions. A good source of information on European traders is The Travels of James Needham and Gabriel Arthur through Virginia, North Carolina, and Beyond, 1673-1674, edited by R.P. Stephen Davis, Jr. 1990. Needham and Arthur are credited as being two of the first traders with the Cherokee Indians.

Needham and Arthur first reached a Cherokee village in 1673, hoping to trade for deerskins and beeswax. Both were initially successful with their trading efforts. However, in a now legendary encounter probably embellished by the passing of time, Needham met his demise at the hands of a Cherokee Indian known as Hasecoll. Hasecoll was also known as “Indian John.” Needham entered into a heated exchange of words with Indian John on a trail near the Yadkin River in June 1674. To bring their long-heated argument to a conclusion, Indian John shot Needham in the head, and then took out his knife and cut open Needham’s chest to remove his heart. Reportedly, Indian John stood over the body holding Needham’s still-beating heart high in the air. He then looked defiantly eastward towards the settled English colonies and made a proclamation about his disdain for all English settlers to the region and especially Needham.

Immediately thereafter, Indian John dispatched some of his compatriots to eliminate Gabriel Arthur as well. These compatriots found Arthur, tied him to a stake, surrounded him with “combustible canes,” and attempt to burn him alive at the stake. Except for the intervention of the Cherokee “King,” this would have been the end of Arthur.

It became apparent that trading with the Cherokee could be an extremely dangerous line of work. Although these incidents did not keep European traders from the Cherokee territory, the traders and other European settlers realized that the Cherokee Indians were not to be trifled with. Those brave souls who did enter the Cherokee territory for trading were financially well rewarded. The primary deerskin trade along with other animal skins was in high demand in the colonies and England.

The European trade with the Cherokee Indians and other Indian tribes changed forever the Native American societies that had inhabited the regions for thousands of years. These societal changes came in many forms, with the most basic being the subsistence farmers and subsistence hunters for millenniums who, by the early 18th century, began harvesting tens of thousands of animal skins just for trade.

The European traders were trading all manner of goods for these animal skins. Some of these trade items included cloth fabric, iron and steel pots, and tools, such as steel axes. African American slaves were also traded in these exchanges. Probably one of the most popular trade items was horses, which were reintroduced to North America in 1519 by the Spanish. These were not readily available to Native Americans. Firearms were an extremely popular trade item that eventually caused concern with the colonists, but in the meantime aided the Cherokee in hunting deer for their skins.

Alcohol, whiskey, and rum were popular trade items because Native Americans did not ferment the alcohol and had very little experience with intoxicating beverages. This alcohol trade had far-reaching effects and long-term repercussions for Native Americans. Before the introduction of alcohol, culturally for thousands of years, Native Americans celebrated with dance and sporting activities. After the introduction of alcohol, many of these cultural activities were replaced with alcohol consumption. Alcoholism is a legacy of this original Native American trade from four hundred years ago. A study of Native American deaths from 2006 to 2010 purports that deaths from alcohol-related incidents or behaviors were four times more common with the Native American population than with the general U.S. population.

Without a doubt, the most devastating effect of trading with the Europeans was the exposure to European diseases, to which the Cherokee had no immunity. All Native American tribes were devastated by a number of smallpox epidemics. In just one of these many epidemics, the 1738-39 Smallpox Epidemic, the Cherokee and Catawba Indians lost half of their populations. It was estimated that up to 10,000 Cherokee, reflecting half the total population, died as a result of this epidemic. This epidemic killed an estimated 700 Catawba Indians, which was half of their remaining population that had already been devastated by early epidemics.

Along with devastating epidemics and a shrinking population, the Cherokee had also been contending with European settlers encroaching on their territory in North Carolina and South Carolina. The breaking point with the Cherokee on these territorial encroachments was reached during the American Revolution. What later became known as the Cherokee War of 1776 was a bloody Indian uprising against settlers and settlements in both Carolinas and bordering states. During the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, the British had been seeking alliances with Native American tribes to help them quell the Patriot uprising. Many tribes joined with the British against the Patriots in hopes of protecting their territory from further encroachment.

In July 1776, Cherokee Indians with other allying Indian tribes began fierce and brutal raids on settlers and lone settlements to shocking effect. These Indian raids, at first, concentrated on Appalachian settlements in what was known then as the Washington District. These settlements were located around the Watauga, Holston, Nolichucky, and Doe Rivers. The Washington District eventually became western North Carolina and eastern Tennessee. These Indian raids later spread to the surrounding states of North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, and Georgia.

It is probably safe to say that the fortunate settlers were killed at the onset of these raids. Settlers who were not initially killed were typically subjected to torture and mutilation and then clubbed to death. Once dead, they were then typically scalped. Before the raiding parties left, they would slaughter the livestock, and burn crops and homes. As to be expected, these Indian raids terrified and enraged the Patriot population. Much of the population fled to frontier forts for refuge, while others sought vengeance against the Native Americans.

In retaliation for the Indian raids, the state militias of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia launched a punitive campaign against the Cherokee Nation and their Native American allies. All three state militias totaled approximately 6,000 men. Each state militia advanced on the Cherokee Nation on three different fronts in a three-pronged attack. Some of these militia members were seeking vengeance against the Cherokee for the brutal murders of family, friends, and neighbors. This personal vengeance could be seen in the brutal retaliation dealt out to the Cherokee and Native American people who were in the path of these three militias. The brutality of these Cherokee Indian raids and the resulting public outcry prompted many prominent leaders of the era, including Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, and John Hancock, to demand the elimination of the Cherokee Nation.

Many Patriots, correctly or incorrectly, felt the severe brutality of the Indian raids was done at the behest of the British. The general consensus among the Patriots was that these Indian raids were efforts by the British to wear down Patriot support among the populace. Still, the Cherokee and other Native American tribes purportedly believed that they were well within their cultural norms to repel encroachment by settlers into their territory. If there ever was any evidence of the direct involvement of the British inciting the level of brutality in the raids, it has been lost to history. That being said, the Cherokee and other Native American tribes had been told by the British that they had the right to deal with settlers trespassing in their territories.

The reprisal attacks by the three state militias on the Cherokee Indians and their allies were brutal and disproportionate to the initial Indian raids. Over fifty Indian villages were burned. In tandem with the burning of the villages, unharvested and stored crops were destroyed. The villages were shelter for the coming winter and the crops were food needed for the coming winter. The eventual death toll for both sides in this conflict is not known, but it is believed to be in the hundreds.

By the beginning of 1777, the Cherokee War of 1776 was effectively over, with the exception of some Indian holdouts. These holdouts eventually became known as the “Chickamauga Cherokee,” and were led by Dragging Canoe (c. 1738 – 1792). Dragging Canoe was a Cherokee war chief (skiagusta: Cherokee for war chief), and this band of the Cherokee fought on for years afterward, only ending with the Treaty of Tellico Blockhouse in 1794.

Credited with being the first settlers of European descent to arrive in the future Asheville area was the family of Samuel Davidson in 1784. Samuel Davidson (1737 – 1784), his wife, infant daughter, and a servant girl (conflicting accounts state this was a slave girl) traveled from Davidson’s Fort (i.e., present-day Old Fort) over the Blue Ridge Mountains by way of the Swannanoa Gap. Upon arrival, he built a cabin for his family on the banks of Christian Creek on Jones Mountain. Jones Mountain is located roughly halfway between what would eventually become present-day Asheville and the settlement of Swannanoa. He immediately set to homesteading and planted crops.

Legend has it that Samuel Davidson had tied a cowbell to his horse in an effort to keep up with the animal. One morning, Samuel went out to find his horse by listening for the cowbell. Apparently, a Cherokee raiding party had removed the cowbell and was using it to draw Samuel up the mountain. As Samuel arrived at the trail at the summit of Jones Mountain, he was ambushed. Samuel’s wife heard the shot that killed her husband along with the Indians shouting in celebration of their successful ambush. Taking her infant daughter and the servant girl, she immediately bolted in fear for Davidson’s Fort. Traversing on foot over sixteen miles of very rough mountainous trails, it took the small party almost all day to arrive at Davidson’s Fort by dusk.

Upon arriving at Davidson’s Fort, Samuel’s widow informed everyone of her husband’s demise. Major William Davidson, Samuel’s brother—reportedly his twin brother, but death records indicate separate years of birth—along with other troops took out into the night in response. Samuel’s remains were located at the site of the ambush on top of Jones Mountain. He had been shot dead and then reportedly scalped. His remains were buried on that site and his grave was marked with stones. A granite monument was placed at this ambush site in 1913 inscribed with, “Here lies Samuel Davidson. First white settler of western North Carolina. Killed here by Cherokee, 1784.” This monument and site are located on private property.

The following year, in 1785, a permanent settlement was established in the valley. The population increased so much so that in 1791, Colonel David Vance and William Davidson presented to the North Carolina House of Commons a “petition of the inhabitants of that part of Burke County lying west of the Appalachian Mountains praying that a part of said county, and part of Rutherford County, be made into a separate and distinct county.” The new county petition was turned into a bill and ratified by the legislature on January 14, 1792. The new county, Buncombe, was named in honor of Col. Edward Buncombe, a Revolutionary War hero from Tyrell County, North Carolina. This new county included most of western North Carolina and only had a population of around 1,000 people. The county was so large that it was referred to as the “State of Buncombe.”

The population increase in these early years through the late 1800s was primarily comprised of people of Scot-Irish descent. There was also a large percentage of people of German and English descent who moved into the area during this same period. Before the end of the American Civil War, African Americans came to the area as slaves, and afterward of their own volition, but in lesser percentages than these other ethnic groups or nationalities.

The primary endeavor of the inhabitants of the area was agriculture. This agricultural tradition continued from the early years of settlement, well into the 20th century. In the last thirty years, more and more former farmlands have been reconstituted for residential development.

In 1793, John Burton established a settlement in Buncombe County called Morristown. Burton had received a state land grant of 200 acres. Part of this grant ran on both sides of present-day Biltmore Avenue to Aston Street and College Street. He developed this part of his grant into forty-two half-acre lots. Reportedly, he sold these lots for around $20.00 apiece. Within two years, these same lots were selling for up to $100.00 each. Morristown was incorporated in 1797 as Asheville. The name “Asheville” was derived in honor of North Carolina Governor Samuel Ashe (1725 – 1813).

A U.S. Post Office was established on January 1, 1801, in the town of “Ashville”[sic]. Mr. Jeremiah Cleveland was the first postmaster. The U.S. Post Office Department officially amended the name of “Ashville” to Asheville in 1877.

Transportation or the lack thereof has shaped much of the mountain areas of North Carolina. Asheville’s transportation infrastructure developed at a greater pace than other mountain areas of the state. Before 1828, the only roads to Asheville reaching the outside world were rough wagon trails that were impassable at times. In 1828, the Buncombe Turnpike—a 75-mile road that ran parallel to the French Broad River from South Carolina—was completed. This road opened Asheville to trade with South Carolina and more trade with the west, especially Tennessee and Kentucky. Up to this point in Asheville’s history, this was the most economically impactful. The Buncombe Turnpike from Asheville to Greenville transformed to a plank road in 1851.

The railroad crossed the Eastern Continental Divide and arrived in western North Carolina. In 1881, the Western North Carolina Railroad arrived in Asheville. Before this time, people had to travel to Hendersonville, which had the closest train station. The advent of the railroad into the Swannanoa Valley was a significant economic driver for the area. The railroad brought tourists, land speculators, and more migration of people to Asheville. The railroad was a big economic boost for farmers because it allowed them to ship crops and livestock to faraway markets. The arrival of the railroad and the extensive road system transformed Asheville from a poor rural area to one of North Carolina’s most prosperous by the turn of the 20th century.

In 1830, Robert Henry, a pioneer and Revolutionary War veteran, discovered Sulphur Springs and founded the area’s first health resort. His son-in-law, Reuben Deaver, built a 250-room hotel at the resort. Henry’s resort ushered in what would become another major economic driver for Asheville up to the present times: tourism.

In the 1880s, George Washington Vanderbilt II was a frequent visitor to the Asheville area with his mother Maria Louisa Kissam Vanderbilt. He described the area as the most beautiful place on earth and set about building a home. G.W. Vanderbilt II, the grandson of the legendary Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt, purchased 125,000 acres of land and constructed the Biltmore Mansion. The Biltmore Mansion, also known as the Biltmore Estates and the Biltmore House, is the largest private residence in the United States, at 178,926 square feet.

G.W. Vanderbilt II hired renowned architect Richard Morris Hunt to design the home. Construction began in 1889 with principal construction completed in 1895. The scale of the construction was such that it required the laying of three miles of the railroad line from Asheville to handle all the construction material. The construction required hundreds of skilled craftsmen and laborers to complete the 255-room mansion. G.W. Vanderbilt II employed prominent landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted to design the gardens and grounds. Olmstead also designed New York City’s, Central Park. While the mansion is beyond magnificent, the grounds are just as impressive and are well worth the visit to Biltmore alone. It is believed that the cost of construction and upkeep of Biltmore drained much of G.W. Vanderbilt II’s family inheritance. Around one and a half million people visit Biltmore every year.

In the 20th century, there were a great many resorts and hotels constructed that greatly benefitted the economy of Asheville and the surrounding area. In the early 20th century, three religious retreats were established: Montreat, Ridgecrest, and YMCA Blue Ridge Assembly.

Businessman and real estate developer Edwin Wiley Grove (1850 – 1927) in the early part of the 20th century made major contributions to the development of Asheville. E.W. Grove has been called the “Father of Modern Asheville.” During the 1920s, he started Grovemont, which is reportedly America’s first planned community. Grove created Lake Eden, which was to become a country club for Grovemont. He died before his Grovemont came to fruition. He developed the Grove Arcade in Asheville.

Probably Grove’s most famous and long-lasting contribution to Asheville has been the Grove Park Inn resort, which he opened in 1913. This began in 1909, when Grove purchased 408 acres in Asheville. The resort has developed over the past century as one of Asheville’s major attractions. William Jennings Bryan delivered the keynote speech at the grand opening on July 12, 1913. Bryan in his speech declared that the Grove Park Inn “was built for the ages.” Through the years, the Grove Park Inn has had thousands of guests, including Presidents Calvin Coolidge, Woodrow Wilson, and Franklin Roosevelt; industrialists such as Henry Ford, John D. Rockefeller, and Thomas Edison; entertainers such as Will Rogers and Harry Houdini; and authors such as F. Scott Fitzgerald and Thomas Wolfe, to name just a few of the distinguished visitors.

The Great Depression of the 1930s was disproportionately harsh in Asheville. The Great Depression, which began in 1929, devastated the national and international economies. However, Asheville had enjoyed a booming economy since the turn of the century and had spent and borrowed large sums for infrastructure. This financial distress was compounded when the city’s primary bank, Asheville’s Central Bank and Trust Company, collapsed on November 20, 1930. Plummeting tax revenue, as well as the city and county’s debt, brought them to bankruptcy. Buncombe County tax receipts for 1927, before the Great Depression, totaled around $180 million that year. By 1933, those annual tax receipts had fallen to $80 million. Asheville had the highest per capita debt level of any city in the nation. Politicians and city officials at that time pledged that every municipal bondholder and creditor would be paid in full. The city financially struggled for many years, but finally paid off all of the bondholders and creditors in 1977.

Much of the farmland and surrounding mountains are being developed into residential housing. The economy has shifted away from farming and manufacturing to tourism and other service businesses. There has been an influx of retirees in the region for the past forty years. This trend appears to be steadily increasing. The University of North Carolina at Asheville, and a bustling downtown area with museums, restaurants, and shops, have made Asheville into a cultural mecca for residents and tourists. The ease of access to U.S. Interstates 26 and 40, and the Asheville Regional Airport, have made a once difficult destination to reach, an easy and relatively fast getaway.

Notable People, Places & Events in Asheville:

Pack Square Park in downtown Asheville was the location of the county’s first courthouse. It is described as a “small one-room log courthouse.”

Balm Grove Church (presently Trinity United Methodist Church) located at 587 Haywood Road Asheville, was founded around 1820. Reportedly, radio legend Paul Harvey said of Haywood Road in Asheville that, “There are more churches per mile than any other street in America.” There are now five large churches on Haywood Road.

Asheville’s first fire department was formed in 1882. A hand-drawn fire wagon with ladders, buckets, and firefighting tools was purchased at this time.

In 1886, the telephone first arrived in Asheville.

From 1887 until 1934, the Asheville Street Railway Company operated electric streetcars in Asheville. Asheville was reportedly the second city in the nation to have electric streetcars (with Richmond, Virginia, supposedly being the first to do so in 1886). At the height of this, there were eleven street railways in operation.

Electricity was used to light the streets of Asheville for the first time in 1888. This was accomplished primarily through four one-hundred-foot masts placed at four locations in the city. Each mast had four arc fixtures that flooded the surrounding area with light.

Edwin George Carrier, a real estate developer and businessman, built Asheville’s first amusement park, Carrier Field, in the 1890s. He also formed the French Broad Racing Association at Carrier Field, which eventually became the Asheville Motor Speedway, transforming into a city park.

U.S. President Rutherford Birchard Hayes’ (1822 – 1893) third son, Rutherford Platt Hayes (1858 – 1927), moved to Asheville in 1900. Rutherford Platt Hayes worked with Asheville businessman Edward W. Pearson, an African American, to develop residential neighborhoods for African Americans in Asheville. Rutherford Platt Hayes founded Buckeye Water Company from springs on Deaverview Mountain to West Asheville in 1903.

E.W. Pearson, a Spanish American War veteran, in 1912, developed the Burton Street neighborhood for African Americans. He also founded the Asheville Royal Giants, a semi-pro baseball team.

In 1924, Charles D. Owen, owner of Beacon Manufacturing, purchased approximately four hundred acres of land close to Asheville. This land was for the construction of a new 200,000 square feet cotton blanket manufacturing facility. He moved his cotton blanket manufacturing company to the Asheville area from Bedford, Massachusetts. The initial mill village that was constructed to house mill workers had 100 homes.

A synthetic fiber producer of rayon, the American Enka Company was founded in Asheville by the Dutch company Nederlandse Kunstzijdefabriek (Dutch translation: Netherlands Artificial Silk Company) in 1928. That same year, American Enka constructed their first manufacturing plant in Asheville. Along with the construction of the manufacturing plant, American Enka built a mill village for the plant workers. In the depths of the American Great Depression, American Enka became a leading employer in the area, and by 1933, the plant had expanded and employed 2,500 people. American Enka became the largest manufacturer of rayon in the United States.

Need Association Management?

Contact Us

How to Start

The Process of Working With Us

REQUEST A PROPOSAL

Request a proposal online or call us directly.

WE WILL REVIEW YOUR CASE

Our team of highly trained professionals will review your case.

RECEIVE A CUSTOM TAILORED PLAN

We will create a customized management plan for your community.

SEAMLESS TRANSITION

We will implement a seamless management transition and integrate our tech.

SIT BACK & RELAX

Enjoy better, affordable and a more reliable, hassle-free management system.